Contributor: Crypto Pilote

Training modern AI models has become a real struggle against the laws of physics. Models are getting larger and larger and require the use of many GPUs, all connected together to form something like a supercomputer. To be efficient, exchanges between GPUs must be extremely fast (nanoseconds). At this scale, even the speed of light becomes a bottleneck, and a simple propagation delay between two machines can paralyze training. This is why, until now, the only method has been to stack thousands of accelerators (GPUs) in ultra-dense data centers, connected by state-of-the-art high-speed optical fibers.

Reaching this level of infrastructure complexity is not within everyone’s reach, and only tech giants can afford to finance it. Like every technology, it is first concentrated and then a lot of small units emerge in an incredibly orchestrated network. It was the case with petrol companies, electricity providers, internet companies, cell phones, computers, etc., etc. Often, the first mover is left behind with a ton of debt from R&D.

AI giants know this very well. In a recent public allocation, Jensen Huang, founder of NVIDIA, admitted that it would be a great idea to use excess energy for intelligence. As this is exactly what Bittensor does, Const replied ironically, “cool idea”.

At the same time, Anthropic co-founder Jack Clark publicly announced that he was interested in the new Templar paper on distributed training of AI.

It’s clear that the future of AI will be decentralized, so let’s look at what the decentralized AI training landscape looks like today and how Bittensor plays a key role in the future of AI.

I – The basics to properly understand what follows

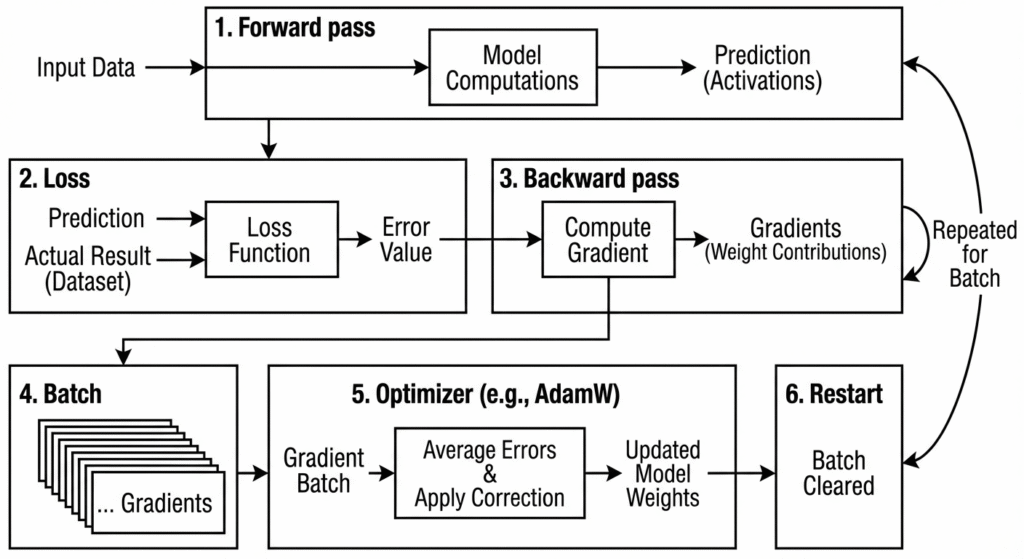

Before getting started, it is important to understand the main stages of classical model training:

Forward pass: The model takes data as input and performs its internal computations to produce a prediction: the activations.

Loss: A mathematical function compares the model’s prediction with the actual result from the dataset in order to measure the error.

Backward pass: The system computes the gradient, meaning the contribution of each network weight to the total error. This is repeated multiple times until a gradient batch is obtained.

Batch: To optimize performance, model weights are updated only after several data points. The batch size is defined in the code and constrained by accelerator capacity.

Optimizer (currently popular: AdamW): All errors are averaged and the necessary correction is applied to the model weights to drive learning.

Restart: The batch is cleared and the process restarts with the new parameters.

If communication between accelerators is not perfectly synchronized (due to excessive latency or a machine issue) the entire system pauses until the information is received. This requirement for speed and physical proximity has until now been an insurmountable barrier, but recent breakthroughs finally make it possible to cross it and open the path toward decentralized AI.

II – The current decentralized architecture

A – NOUS Research (previously SN6)

In November 2023, a Google DeepMind team published a paper demonstrating that it is possible to train an AI while synchronizing model weights only very rarely (every 500 or 1000 steps): DiLoCo (Distributed Low-Communication).

One year later, Nous Research released a concrete proof. A model capable of matching the standard while reducing the number of communications between machines, thus enabling the training of large models over a heterogeneous network with slow connectivity.

Building on existing discoveries, Nous proposed three conjectures that they cannot formally prove but that hold empirically:

- Changes that move strongly are generally correlated with each other.

Therefore, less information can be sent because it is redundant. - Large changes show little volatility over time and should be corrected first. Conversely, small changes are highly volatile and are more relevant when treated later.

- Small changes are essential to the model’s learning and must be preserved.

To better visualize this, you can imagine a sculpture. Large blocks can be removed at once to shape the main lines (1). You start with that to gain efficiency (2), and you keep the details for the end, as they give the work its full dimension (3).

Based on these observations, they designed a decentralized model: DeMo – Decoupled Momentum Optimization.

It runs like this:

- Local training

The miner will train its model without communicating with other miners for several cycles (between 500 and 1000). It will then take stock of the modifications made to the model.

- Sorting / compression

Once the assessment is done, the significant changes must be sorted. The Kosambi–Karhunen–Loève Transform (KLT) theorem allows this, but it is very computationally expensive and therefore incompatible with a decentralized network.

Nous Research therefore turned to another computation method, the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT), which is capable of providing a sufficient approximation. Fun fact: this is the compression used for JPEG images.

- Refinement

To further optimize exchanges between machines, not all of the signal is transmitted.

DeMo therefore keeps only 1 to 3% of the largest changes. This is top-k sparsification. Following the logic of conjecture 2, the small changes that are not retained will accumulate over time until they become large enough to be processed.

- Sharing

The miners then exchange their compressed results with each other via a P2P network (Iroh)..

- Synthesis of all participants’ modifications

Using the exchanged information, the miners synthesize the changes made by all miners to form the new base model.

The entire system is coordinated by the coordinator through the client installed on the miners’ machines.

The results are striking. Empirically, Nous succeeded in training a 1B-parameter model (and later a 36B model) just as efficiently, without increasing training time, and sometimes even achieving better benchmark results than a centralized model.

With this demonstration, Nous Research paved the way, and soon others followed.

B – Templar (SN3)

A few months later, Templar pushed the limits even further and created Heterogeneous SparseLoCo. An architecture both innovative and efficient that enables training models on machines with varying computational power across the Bittensor network.

Decentralized training means not every machine is necessarily high-end. To accommodate everyone, Templar mixes different miners: datacenters with powerful machines and clusters of smaller, less powerful machines. As small machines cannot store the whole model in their memory, it is sometimes necessary to split the model into multiple parts across a cluster.

Within a datacenter, GPU communications are optimized, as we saw in the introduction. This high-quality connection allows for maximum data retention and finer weight adjustments (gradients) which will be useful later.

This is not the case for clusters made of less powerful and geographically dispersed machines. In such clusters, each machine processes part of the information and passes it to the next miner for further processing. A way must be found to keep all miners in sync regardless of their power, otherwise they would spend all their time waiting.

To maintain the same cadence (i.e., the transmission delay of activations and gradients between miners of a model), data is compressed according to each miner’s bandwidth. Miners in a cluster of small machines can therefore communicate to share the model without slowing down the overall progress of other clusters, contributing equally to the training.

Data is compressed according to a simple principle based on Nous Research’s conjecture 1. Most changes tend to move in the same direction. Therefore, the information can be generalized and a simplified version can be sent, which is much faster to transmit. This is called Subspace Low-Rank Projection compression. It’s a bit like sending a 2D image of a 3D object: not all details are transmitted, but the important information is preserved.

Furthermore, to optimize training time even more, each cluster does not process the same section of the dataset (data parallelism). They need to communicate so that the global model can evolve and prevent each group from drifting too far apart. It’s like a regular checkpoint. However, the model is heavy to send. Therefore, the learning is shared not at every pass, but after a certain number of activation/gradient passes: a batch.

To maintain a consistent pace among participants, clusters with weaker connections compress their data so as not to slow down others. Some model corrections are therefore less precise, as information is simplified during compression. After that, only 1 to 3% of the most important weight changes from a cluster are transmitted. The details (the parts omitted by compression) are not erased. They are stored in the cluster’s Error Factor (EF) and accumulated at each cycle. As a result, small changes grow over time and eventually get sent to the global server later in training.

Meanwhile, the most advanced clusters, which can afford to send their model to the central server with little or no compression without slowing down overall training, serve as a reference to prevent hallucinations and artifacts caused by accumulated compression errors.

Both compressed and uncompressed versions of the model are sent to a central server, which is responsible for completing the compressed data by adding uncompressed data from the “pro” clusters (datacenters) and applying modifications (optimizer – AdamW) to the global model before sending it back to everyone for the next batch.

Based on their participation, miners then receive their Bittensor network reward for the work performed.

Thanks to this method, they succeeded in training a 72B-parameter model on January 21, 2025, a first in the world of decentralized training and an engineering feat that promises a bright future for Templar.

C – IOTA (SN9) – INCENTIVISED ORCHESTRATED TRAINING ARCHITECTURE

IOTA proposes a relatively similar approach but manages to do without a central server for model aggregation thanks to three major pillars: the Bottleneck Transformer Block, weight sharding, and the Orchestrator. Let’s look at these in detail.

The main difference lies in the model distribution and its consequences. Normally, the model is replicated by fragmenting it within a machine cluster (pipeline parallelism). With IOTA, each miner layer only holds a fraction of the model, and all miners within a layer have the same fraction. The model is therefore not replicated multiple times but segmented into several miner layers. This is called tensor parallelism. In addition to that, they use SWARM technology to manage flows between layers and miner sIt allows the model to be highly adaptive, for example in the event of a miner failure or to adjust the power requirements between the layers of the model.

This is clever because it lowers the technical barrier by dividing the model according to the number of available miners. This approach is particularly scalable, as any machine (even a MacBook) can take a fragment of the model corresponding to its capacity. The more machines there are, the larger the model can be.

To help conceptualize this, imagine a large assembly line with several workers at each key station.

If they were building cars, then layer 1 (5 miners) would assemble the chassis for 5 different cars at once, layer 2 the wheels, layer 3 the paint, and so on. At the end of the line, the last layer checks the results against the order (dataset) and sends feedback to the previous layers for correction. Layer 2 might receive the instruction: “the wheels were not tightened properly,” and it could report to layer 1: “the chassis was warped, I attached my wheels incorrectly.” This way, each layer can improve, thereby improving the global model.

Although the model is brilliant, the communication speed between layers and miners remains critical for achieving satisfactory results. Unsurprisingly, IOTA uses compression to gain speed over an often slow internet network.

And if you already found this approach clever, let me introduce you to the Butterfly All-Reduce (BAR) and the Bottleneck Transformer Block (BTB).

Butterfly All reduced (between miners within the layer)

- When a minimum number of miners in a layer have processed their data, synchronization is triggered. Each miner splits its compressed delta gradients (the difference between its weights before and after the series) into shards. Those who have not finished before this threshold are not taken into account and will need to update themselves with the delta from the others.

- The Orchestrator then randomly pairs miners and distributes the shards to the pairs. Each miner calculates the average of the shards it is responsible for and compares it with the other miner in the pair. If the results differ, it means that one of the miners is malfunctioning or cheating and will be penalized by the Orchestrator.

- If the comparison is correct, each miner downloads the updated version of the shard to reconstruct the “Global Delta” of the model fragment.

In the same way as with Nous and Templar, miners train locally on a batch before synthesizing their progress (DiLoCo).

If a miner is too slow or disconnects and desynchronizes from the others, its work is wasted. It is not financially rewarded, as its work did not contribute to the others. In the most extreme cases, if uptime issues persist, the miner can be ejected.

Bottleneck Transformer Block (between the layers)

Normally, models use quantization to compress data. Quantization is a compression mechanism that reduces the precision of data by shrinking the space it occupies (for example, from 32-bit to 8-bit). The limitation of this technique is that it creates approximations and treats all information the same way—important and insignificant alike. Critical data can be lost, even though less important data could have been sacrificed during training instead.

To avoid losing valuable information during layer-to-layer compression, IOTA does it in two steps:

- Addition of a compression/decompression model based on Llama3 to filter and retain only the important data (size reduced by a factor of 64).

- Light quantization: 32-bit → 16-bit (size reduced by a factor of 2).

This “filtering” model also preserves the Residual Path, a channel that transfers the most important data without compression, like a priority lane on a highway. Critical information travels uncompressed on the priority lane, while the rest is reduced to optimize speed. The mini-model thus acts as a buffer between layers, ensuring that information can be transmitted without signal loss and without slowing down training.

Thanks to this unique solution, IOTA is able to compress activations/gradients between layers by a factor of 128x without affecting training (convergence) and while avoiding the loss of critical signals that would otherwise break learning (gradient vanishing).

Orchestrator :

Finally, the Orchestrator intervenes at multiple levels to regulate and ensure that all layers (and thus the model) remain coherent and efficient, as its name suggests:

- Distribution

Miners are distributed according to the complexity of the layer. The Orchestrator decides how many miners to assign to a layer and manages miner disconnections and failures. It also manages the data flow to ensure that all information is transmitted between layers without interruption. - Triggering

It also acts as the training clock. It triggers the shard process when a portion of miners has finished processing a minimum amount of data. - Sharding

During the aggregation of learning, miners split their weights into multiple shards. The Orchestrator assigns these shards to several miners for synthesis. This also allows it to detect bad actors if the synthesis of the same shard differs between two miners. - Reward

Since IOTA runs on Bittensor, the Orchestrator also measures the participation of different miners and excludes bad actors. Good miners can then be paid in alpha for their efforts. The system, called CLASP (Contribution Loss Assessment via Sampling of Pathways), is still being finalized and will be deployed in the final product.

These additions form the core of IOTA’s engineering, which has been successfully tested on a 14B-parameter model.

By splitting the model into multiple layers rather than by machine within a cluster, it is possible to train potentially very large models while maintaining high execution speed thanks to the novel compression methods. For now, the system is in beta, and around 300 machines have joined the network, but new slots should be available soon.

III – Conclusion

In just three years, decentralized model training has made huge leaps, going from a few million parameters to tens of billions. Each solution demonstrates remarkable ingenuity, which will, in the future, democratize model training and allow teams around the world to create their solutions without bearing the enormous burden of infrastructure.

Beyond the scientific interest, this emerging technology is already attracting the biggest players, and Bittensor stands out (once again) thanks to the quality of its participants. The progress of each project will need to be followed closely, as the journey is only just beginning.

Only on Bittensor.

Be the first to comment