At CES 2026, Nvidia did not just introduce a new generation of chips; it quietly reframed how AI will be built, deployed, and priced over the next decade.

With Rubin, Nvidia is pushing AI away from scarce, bespoke systems and toward something closer to industrial infrastructure. Inference becomes cheaper, memory-heavy workloads become routine, and deploying thousands of specialized models becomes economically viable.

That shift has second-order consequences.

As AI becomes abundant and modular, the challenge is no longer how to run models; it is how to organize them. This is where open intelligence markets like Bittensor begin to matter.

Rubin Signals a Structural Shift in AI Infrastructure

Rubin is Nvidia’s next-generation data center platform following Blackwell. Unlike earlier architectures that focused on individual accelerators, Rubin treats the rack itself as the computing unit.

The system integrates several components into a tightly coupled whole:

a. Next generation GPUs (Graphics Processing Units),

b. High-bandwidth HBM4 memory,

c. Custom CPUs (Central Processing Units), and

d. Ultra-fast interconnects.

By reducing data movement and improving memory locality, Rubin dramatically lowers the cost of running large models, long-context inference, and reasoning-heavy workloads.

In practical terms, Nvidia is no longer selling chips; it is selling AI factories.

This matters because modern AI systems increasingly rely on many interacting models rather than a single monolithic one.

Cheaper Inference Changes How AI Gets Built

When inference costs fall, architectural decisions change. Developers no longer need to compress every capability into one large model.

Instead, they can deploy many smaller, fine-tuned models that each handle a narrow task well. This enables:

a. Agent-based systems where models call each other,

b. Domain-specific models optimized for particular workflows, and

c. Real-time orchestration across multiple intelligence providers

However, abundance introduces a new problem. Once there are thousands of models available, someone has to decide which one gets used, when, and why.

Cloud providers can host models, but they do not offer neutral mechanisms for ranking performance or distributing rewards across competing intelligence.

The Coordination Gap in an Abundant AI World

As AI becomes modular, three coordination challenges emerge. They are:

a. Selection: asking which model should handle a given request,

b. Evaluation: addressing performance should be measured over time, and

c. Incentives: looking at how value should be distributed fairly.

Centralized platforms solve this by ownership and control. They pick the models, define the metrics, and capture the upside.

That approach works when models are scarce but breaks down when intelligence becomes abundant and distributed across organizations, regions, and clouds.

This is the gap Bittensor is designed to fill.

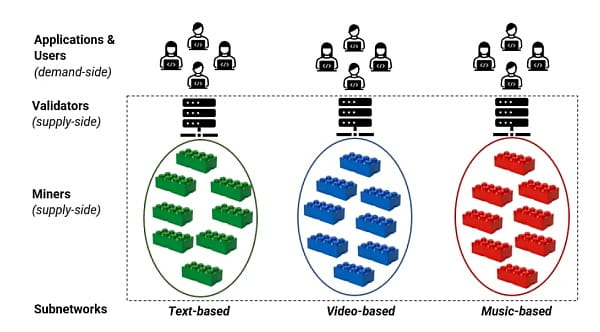

How Bittensor Turns Models Into a Market

Bittensor operates as a decentralized network of subnets that allows AI models to compete in providing useful outputs. Rather than trusting a single platform, the network uses on-chain mechanisms to rank models based on performance.

Those rankings directly determine how rewards are distributed in its native coin, $TAO. Also, each subnet functions as a focused market for a specific type of intelligence, such as:

a. Text generation,

b. Image understanding,

c. Data analysis,

d. Specialized domain inference, amongst others

Models that perform well gain influence and rewards and those that underperform are naturally deprioritized. As the number of available models grows, this market structure becomes more valuable, not less.

Why Rubin Makes Bittensor More Relevant, Not Less

Rubin does not compete with Bittensor, it enables it.

By lowering the cost of inference and memory-intensive workloads, Nvidia makes it easier for developers to deploy specialized models at scale. That increases the supply of intelligence, but supply without coordination leads to fragmentation.

Bittensor provides the missing layer that organizes this abundance; it does not care where models run or who owns the hardware; it cares about measurable usefulness.

In simple terms:

a. Nvidia controls the physical layer of AI,

b. Rubin makes intelligence cheap and abundant, and

c. Bittensor coordinates, ranks, and prices that intelligence.

As AI systems evolve toward agent swarms and modular services, the economic layer becomes harder to centralize. Open coordination starts to outperform closed platforms.

What This Means for 2026 and Beyond

Rubin’s rollout in 2026 will expand AI capacity across data centers and cloud providers. That expansion will increase the number of models competing for real-world workloads.

Open networks like Bittensor are positioned to benefit from this shift. They do not replace Nvidia’s infrastructure; they give it a market.

As AI becomes infrastructure, intelligence itself becomes a commodity that needs pricing, ranking, and incentives. While Rubin accelerates that transition, Bittensor gives it structure.

In that sense, Nvidia’s most advanced chips may end up strengthening decentralized AI rather than undermining it.

Be the first to comment